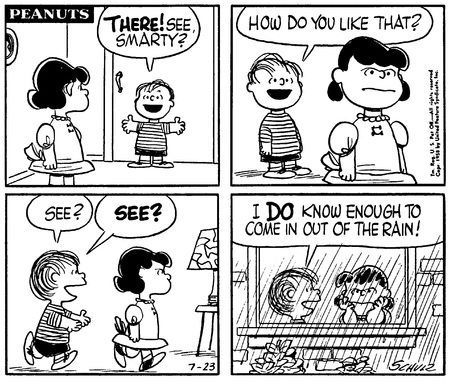

welcome or threat, a

sympathy for the future

hankering for past

What will tomorrow bring.

Why did yesterday have to be left behind?

Maybe tomorrow will be better.

Maybe yesterday was as good as it gets.

I like to read the books of Bernard Cornwell.

His Sharpe Series is a great way to learn about the war in Spain against Napoleon.

I have reread these books several times.

The Last Kingdom or Saxon Stories are absorbing enough though after 13 books its hard to not start flipping through the battle scenes to get to the character narrative.

Not meant as a criticism but I find myself reading through the books and hitting some passages and that scene from the movie, ‘Amadeus’ comes to mind when Mozart plays a short piece of music written by Antonio Salieri after just one hearing.

Young Mozart picks his way through the first couple of bars, squints off into the middle distance and mutters, ‘The rest is just the same, isn’t it?”

Cornwell’s Warlord Chronicles are an interesting take on the Arthurian Legends and Arthur as a reluctant hero.

I think Mr. Cornwell is a bit hard on Christians but I think I can discern between his take on Christians as portrayed in the life Galahad and professional organized religion as portrayed by everything else church related in the three novels.

Also the in depth examination of the old ‘norse’ ways does tend to make me uncomfortable but I take the long road here as I know who historically wins this argument.

Some of the best scenes are the also repeated in the Saxon Series, where the folks come across Roman ruins of villas, baths and bridges.

They look over the ruins and say, “how did they do this?”

Knowledge can be lost so easily.

I hate to think what happens to the modern library without electricty.

The great libraries prior to 1900, those wonderful, vast reading rooms like you see in Univ of Michigan Hatcher Library or even the Grand Rapids Michigan Main building were all designed to use natural lighting from windows.

The roofs were giant skylights.

The floors were thick translucent glass.

Then came Tom Edison and electric light.

Much like how it took the Wright Brothers 3 hours to get the engine on the first Wright Flyer running the morning they invented flight so they actually invented flight delay first, Tom Edison wired America with power but he also invented the power outage.

ANYWAY, the three books tell the story of Arthur once again.

And you can’t tell the story of Arthur with telling the story of Merlin.

Throughout the three novels, Merlin has a line.

Wyrd bið ful āræd.

Fate is inexorable.

Tomorrow is coming.

Yesterday is gone.

Time and tide sweeps the beaches twice a day here.

How can anything not be new?

That might be welcome news.

That might be a threat.

We ate out last night ate one of our favorite local restaurants.

We like it as it good, local and somehow holds the line against charging resort area prices.

I would say its cheap or at least cheaper.

Last night they had new menus.

Not only new menus, but new dishes.

We searched the menu for our favorites and with the help of the waitress we came close.

Close but not the same.

Throughly enjoyed our dinner.

Wistfully, a little part of our brain, wanted our favorites back.

We understood the need for a fresh menu.

We had sympathy for the future.

We had a hankering for the past.

Wow.

All we wanted was dinner.

Wyrd bið ful āræd.

######

Adapted from the book, The Architecture of Happiness (2009, Vintage Books) by Alain de Botton, and the passage:

However, there might be a way to surmount this state of sterile relativism with the help of John Ruskin’s provocative remark about the eloquence of architecture.

The remark focuses our minds on the idea that buildings are not simply visual objects without any connection to concepts which we can analyse and then evaluate.

Buildings speak – and on topics which can readily be discerned.

They speak of democracy or aristocracy, openness or arrogance, welcome or threat, a sympathy for the future or a hankering for the past.

What Ruskin is quoted as saying is:

‘A day never passes without our hearing our architects called upon to be original and to invent a new style,’ observed John Ruskin in 1849, bewildered by the sudden loss of visual harmony.

What could be more harmful, he asked, than to believe that a ‘new architecture is to be invented fresh every time we build a workhouse or parish church?

According the The New York Review of Books, this is “A perceptive, thoughtful, original, and richly illustrated exercise in the dramatic personification of buildings of all sorts.”

What I find irrestible in reading Mr. de Botton is his use of language.

I get the feeling that if you made a spread sheet of all the words, adverbs and adjectives used by Mr. de Botton, you just might find that he used each word just once.

Neat trick in writing a book.

If I knew how to do that, I would.