misanthropy plus

anger characteristic

bleak fatalism

In 1930, James Thurber published a book of drawings titled The Last Flower.

In Thurber’s New Yorker Obituary, EB White wrote. “Although he is best known for “Walter Mitty” and “The Male Animal,” the book of his I like best is “The Last Flower”. In it you will find his faith the renewal of life, his feeling for the beauty and fragility of life on earth.

One week after publication, Life magazine ran a two spread of the drawings and captions under the headline, Speaking of Pictures … Thurber draws a parable on War, that told the story of The Last Flower.

Right now, today, I need a shot of faith the renewal of life, and in a feeling for the beauty and fragility of life on earth.

This is the Life Magazine introduction to the drawings.

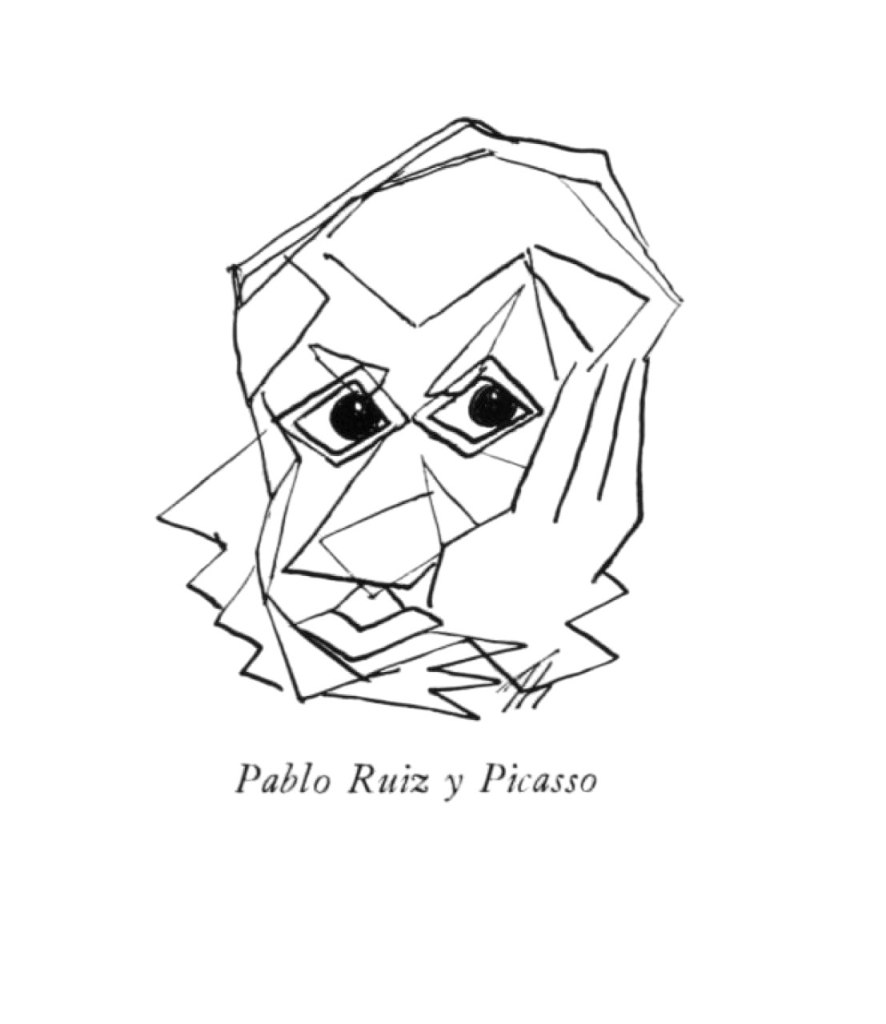

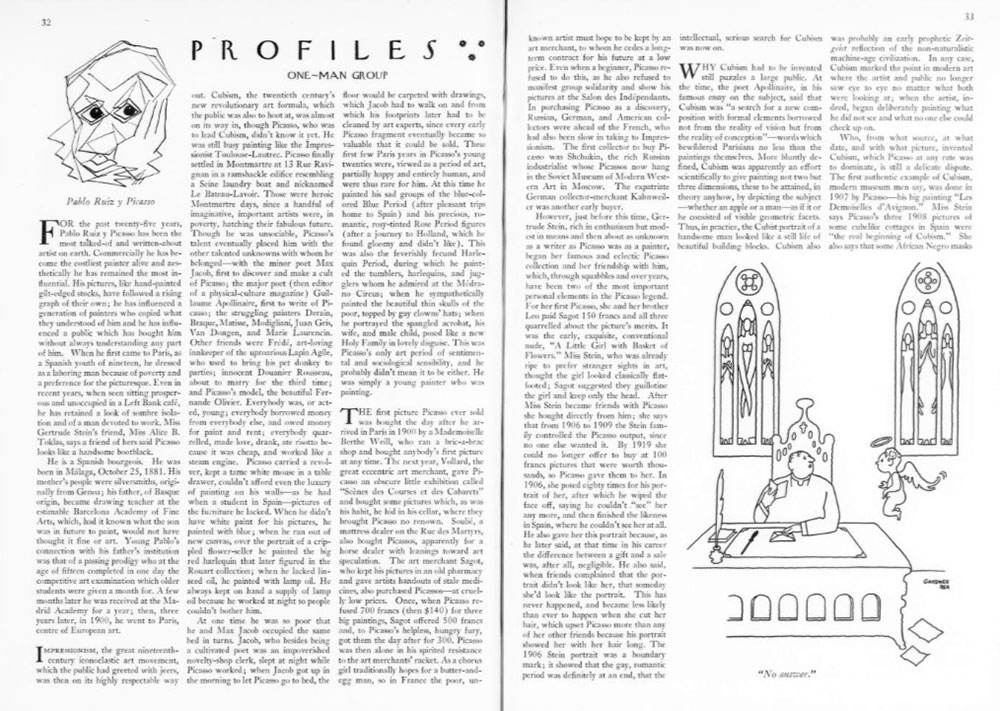

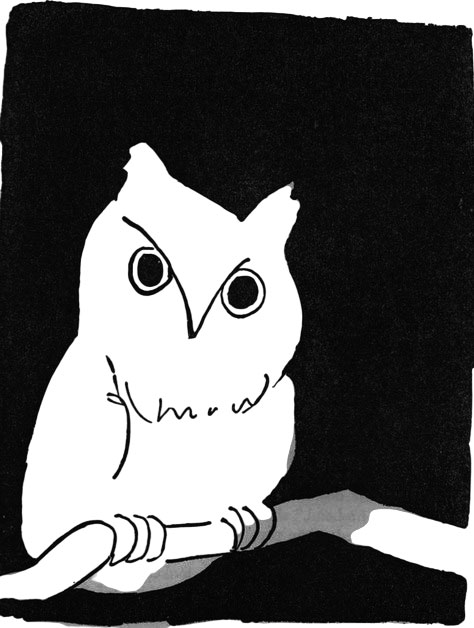

The world of James Thurber is a stark soggy word of predatory women, bald bitter little men and melancholy hounds. Created idly on memo pads, long ignored by the New Yorker and doubtfully put into print in 1931, the Thurber cosmology has since been hailed as the creation of a high satirical intelligence. Art critics applaud his economy of line, call him a successor to Picasso and Matisse.

Beneath his cynicism Thurber is an intense, compassionate liberal. When war exploded in Europe he was moved to produce a “parable in pictures,” packed with his characteristic misanthropy plus anger plus a certain bleak fatalism. At his request Harper & Brothers withheld another Thurber volume then ready for release and rushed The Last Flower ($2) into print. Published on Nov. 17, it is sure to land on many a Christmas tree. Below are some of the 50 drawings from the book, with Thurber captions.

You can see the drawings on my James Thurber page, For Muggs and Rex.