never known woman

who could weep about her age

way men I know can

Well, the characteristic fear of the American writer is not so much that as it is the process of aging.

The writer looks in the mirror and examines his hair and teeth to see if they’re still with him.

“Oh my God,” he says, “I wonder how my writing is. I bet I can’t write today.”’

The only time I met Faulkner he told me he wanted to live long enough to do three more novels.

He was 53 then, and I think he has done them.

Then Hemingway says, you know, that he doesn’t expect to be alive after sixty.

But he doesn’t look forward not to being.

When I met Hemingway with John O’Hara in Costello’s Bar 5 or 6 years ago we sat around and talked about how old we were getting.

You see it’s constantly on the minds of American writers.

I’ve never known a woman who could weep about her age the way the men I know can.

From Interview: THE ART OF FICTION: JAMES THURBER.

Paris Review, 3 (Fall, 1955), 34-49. Illustrated

This snippet made laugh.

I could picture Thurber in his mid 50’s, sitting in a bar with Mr. Hemingway and Mr. O’Hara and that alone is a picture to make me smile.

And that they were worrying about how old they were getting and that Mr. Thurber thought it was funny to the point of saying “I’ve never known a woman who could weep about her age the way the men I know can,” is but itself funny enough to make me laugh out loud.

For sure Mr. Thurber, who was being interviewed for this interview by George Plimpton, was having a great time tossing off the names of Faulkner, Hemingway and O’Hara with the confidence that he COULD toss off these names.

(I am reminded of the a story of Hollywood Movie Director John Ford going on a duck hunt with Clark Gable and William Faulkner and the conversation got around to writing and Gable says to Faulkner, ‘Who are the best writers right now?” Faulkner replies, “Oh Hemingway, Fitzgerald, Steinbeck … and myself.” Gable says “Oh, Mr. Faulkner, do you write?” “Yes,” says Faulkner, “Mr. Gable … what do you do?” … The kicker is John Ford swore both were on the level.)

BUT I DIGRESS …

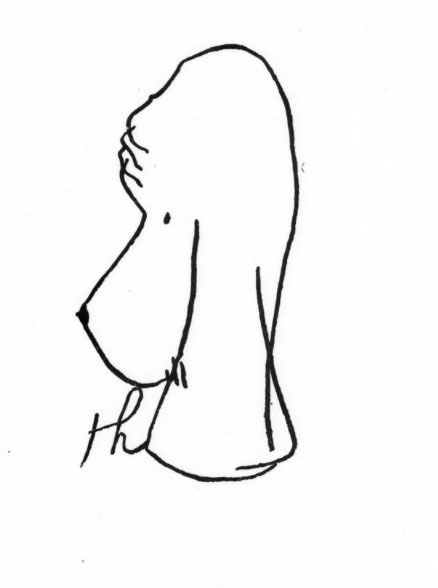

As a kind of post script to the James Thurber story, The Paris Review included this photo.

Notice the caption.

Notice it says CONSIDERABLY REDUCED.

By 1961, James Thurber was pretty much blind in both eyes.

One eye was damaged playing William Tell when he was a kid and the other eye went due to sympathetic eye syndrome.

When he died, EB White wrote in his New Yorker Magazine Obituary:

I am one of the lucky ones; I knew him before blindness hit him, before fame hit him, and I tend always to think of him as a young artist in a small office in a big city, with all the world still ahead. It was a fine thing to be young and at work in New York for a new magazine when Thurber was young and at work, and I will always be glad that this happened to me.

His mind was never at rest, and his pencil was connected to his mind by the best conductive tissue I have ever seen in action. The whole world knows what a funny man he was, but you had to sit next to him day after day to understand the extravagance of his clowning, the wildness and subtlety of his thinking, and the intensity of his interest in others and his sympathy for their dilemmas — dilemmas that he instantly enlarged, put in focus, and made immortal, just as he enlarged and made immortal the strange goings on in the Ohio home of his boyhood.

He was both a practitioner of humor and a defender of it. The day he died, I came on a letter from him, dictated to a secretary and signed in pencil with his sightless and enormous “Jim.” “Every time is a time for humor,” he wrote. “I write humor the way a surgeon operates, because it is a livelihood, because I have a great urge to do it, because many interesting challenges are set up, and because I have the hope it may do some good.” Once, I remember, he heard someone say that humor is a shield, not a sword, and it made him mad. He wasn’t going to have anyone beating his sword into a shield. That “surgeon,” incidentally, is pure Mitty. During his happiest years, Thurber did not write the way a surgeon operates, he wrote the way a child skips rope, the way a mouse waltzes.

Thurber looked in the mirror and asked I bet I can’t write today and then spit in the mirror and said I am going to write anyway.

And he did.