though we achieved a

first-rate tragedy, tragedy

was not our business …

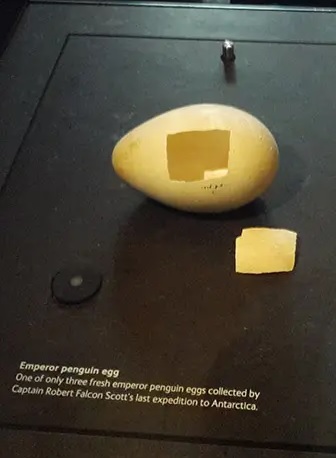

It was all those eggs you see?

According to Wikipedia, It was thought at the time that the flightless penguin might shed light on an evolutionary link between reptiles and birds through its embryo. As the bird nests during the Antarctic winter, it was necessary to mount a special expedition in July 1911, from the expedition’s base at Cape Evans, to the penguins’ rookery at Cape Crozier. Wilson chose Apsley Cherry-Garrard to accompany him and Henry R. Bowers across the Ross Ice Shelf under conditions of complete darkness and temperatures of −40 °C (−40 °F) and below. All three men, barely alive, returned from Cape Crozier with their egg specimens, which were stored.

It was this winter journey, not the later expedition to the South Pole, that Cherry-Garrard described as the “worst journey in the world”

When Mr. Cherry- Gerrard came to write about this trip to get penguin eggs, the book was in fact titled, The Worst Journey in the World.

In the opening preface, Mr. Cherry-Gerrard writes, “Polar exploration is at once the cleanest and most isolated way of having a bad time which has been devised.”

It is an incredible read and no less incredible when it is realized it is all true and written in the first person by someone who had been there.

While the story itself would captivate, the writing of Mr. Cherry-Gerrard is a wonder to enjoy.

Mr. Cherry-Gerrard was not in condition after this side trip to take part in the Captain Scott’s push to be first at the South Pole.

You may remember that while Scott reached the pole, what he found was a note from Swedish explorer Roald Amundsen that he had already been there.

Scott and his part all died on the trip back to camp.

Mr. Cherry-Gerrard led the team that discovered the bodies.

Between the egg adventure and writing the book, World War One took place.

Mr. Cherry-Gerrard closes his book with these passages:

This post-war business is inartistic, for it is seldom that any one does anything well for the sake of doing it well; and it is un-Christian, if you value Christianity, for men are out to hurt and not to help — can you wonder, when the Ten Commandments were hurled straight from the pulpit through good stained glass.

It is all very interesting and uncomfortable, and it has been a great relief to wander back in one’s thoughts and correspondence and personal dealings to an age in geological time, so many hundred years ago, when we were artistic Christians, doing our jobs as well as we were able just because we wished to do them well, helping one another with all our strength, and (I speak with personal humility) living a life of co-operation, in the face of hardships and dangers, which has seldom been surpassed.

I shall inevitably be asked for a word of mature judgment of the expedition of a kind that was impossible when we were all close up to it, and when I was a subaltern of 24, not incapable of judging my elders, but too young to have found out whether my judgment was worth anything.

I now see very plainly that though we achieved a first-rate tragedy, which will never be forgotten just because it was a tragedy, tragedy was not our business.