crimson light of a

rising sun fresh from creative

burning hand of God

According to Wikipedia, This Week Magazine was a nationally syndicated Sunday magazine supplement that was included in American newspapers between 1935 and 1969. In the early 1950s, it accompanied 37 Sunday newspapers. A decade later, at its peak in 1963, This Week was distributed with the Sunday editions of 42 newspapers for a total circulation of 14.6 million.

When it went out of business in 1969 it was the oldest syndicated newspaper supplement in the United States. It was distributed with the Los Angeles Times, The Dallas Morning News, The Plain Dealer (Cleveland, Ohio), the Boston Herald, and others. Magazine historian Phil Stephensen-Payne noted, “It grew from a circulation of four million in 1935 to nearly 12 million in 1957, far outstripping other fiction-carrying weeklies such as Collier’s, Liberty and even The Saturday Evening Post (all of which eventually folded).”

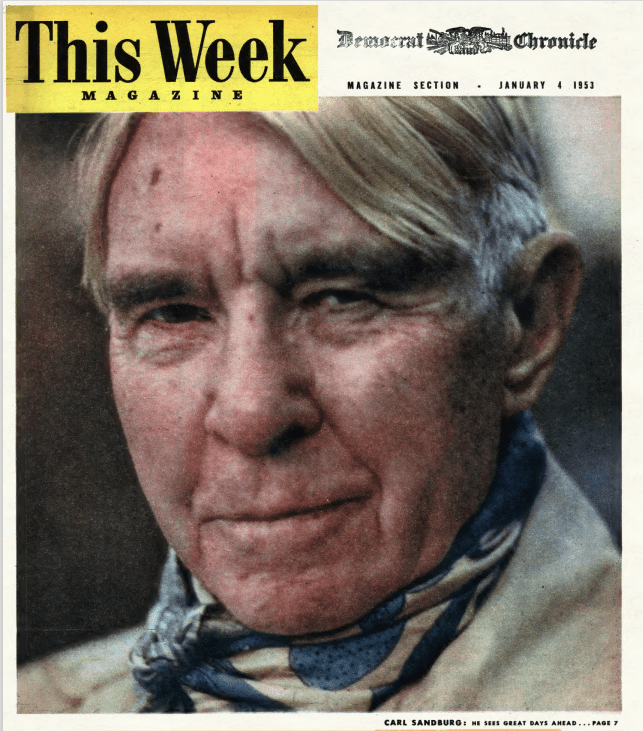

On January 4, 1953, the cover story for This Week was an interview with Carl Sandburg on the occassion of Mr. Sandburg’s 75th birthday and that story became famous for one quote.

That quote is:

“I see America, not in the setting sun of a black night of despair ahead of us, I see America in the crimson light of a rising sun fresh from the burning, creative hand of God.

I see great days ahead, great days possible to men and women of will and vision”

The text of the complete quote is even better at least for those who like to hope for better days,

“I have spent,” he said gravely, “as strenuous a life as any man surviving three wars and two major depressions, but never, not for a moment, did I lose faith in America’s future.

Time and time again, I saw the faces of her men and women torn and shaken in turmoil, chaos, and storm.

In each Major crisis, I have seen despair on the faces of some of the foremost strugglers, but their ideas always won.

Their visions always came through.

“I see America, not in the setting sun of a black night of despair ahead of us,

I see America in the crimson light of a rising sun fresh from the burning, creative hand of God.

I see great days ahead, great days possible to men and women of will and vision. . . “

I end with the last line of the story.

He took off his hat, as if saluting the future, and ran his hand through his white hair and said with a smile, “May I offer my favorite toast? “To the storms to come and the stars coming after.”

To the storms to come and the stars coming after!

I like that.

I like that a lot, especially on a morning when I drove to work as the sun rose out of the Atlantic Ocean with a storm coming from the west.

To close, may I offer Mr. Sanburg’s favorite toast?

“To the storms to come and the stars coming after.“

*I reproduce the story best I can but if you click on this link, you can read a PDF of the complete issue. The advertisements are great and you might enjoy taking the Are You in the Know quiz.

Carl Sandburg Speaking: I See Great Days Ahead

Here is an article that will bring you a thrill. In it, you will walk along a city street with a beloved story-teller, and hear America talking

BY FREDERICK VAN RYN

Mr. Van Ryn, is a former editor and motion-picture executive who has been associated with Sandburg for 20 years.

SEVENTY-FIVE years ago this coming Tuesday, a child was born in a three-room frame house on Third Street, just east of the Chicago, Burlington & Quincy tracks, in Galesburg, Ill. A Swedish midwife said to the dark,

stickily built man who was waiting outside, “Det är en pojke” — “It’s a boy.” The man nodded, ate his breakfast in silence, and went out to his job in the CB&Q blacksmith shop. He was good at swinging a hammer, but he was not very demonstrative.

The boy was christened Carl August Sandburg but he dropped his middle name. The various jobs he tried — he delivered milk and newspapers, he was a hobo and a dishwasher, a shoeshine boy and a soldier — did not seem to rate a middle name.

A few weeks ago, while on a short visit to New York, Sandburg went for a long walk with an old friend. He was in a reminiscent mood. He talked of his early days in Galesburg, of his youth in and around Chicago, of his present home in the mountains of North Carolina, and of America’s future.

The Prophecy

So stirring was his description of the days that lie ahead of us, that his companion wished that all Americans, particularly those who suffer because of little faith, could hear this prophecy of things to come.

Sandburg was not making a speech, he was merely chatting. But it so happens that his conversational style is an amazing mixture of grave, sonorous phrases that seem to be lifted right out of “Pilgrim’s Progress” and the latest slang expressions that would be understood by the most boisterous of teen-agers. Once in a while, as he and his companion were waiting for a traffic light to change, a passer-by would look at Sandburg and say: “Excuse me, but your face seems familiar. Weren’t you on television a few nights ago?” This far-from-flattering way of identifying one of America’s most famous poets and the greatest biographer of Abraham Lincoln did not disturb Sandburg. He grinned. “I like New York,” he said, “but Lordy, oh Lordy, how I miss Chicago . .. New York is handsome and intelligent, but,” he raised a warning finger, “Chicago is steaks, pork chops, grain. When New York is sick, the rest of the country still struggles along, but let Chicago sneeze … why, the whole country runs a fever . . . New York may be this nation’s head, but Chicago is still its heart.

“ Country Boy”

“Why don’t I live in Chicago? That’s simple … I’m a country boy. When I wake up in the morning, I’ve got to be able to see either the prairie or the mountains. When I’m in a city, I feel like a visitor . . . I’m not certain of myself, I can’t think.” He stopped abruptly, raised his head, and looked at the group of massive buildings ahead. _“The Medical Center,” he said slowly. “Each time I look at those beautiful buildings, I think of the miracles that have occurred in America within my lifetime. You don’t hear nowadays about many children dying of diphtheria, do you? Well, when I was twelve, in Galesburg, my two kid brothers, Freddy, who was two years old, and Emil, who was seven, woke up one morning and complained of sore throats. Old Doc Wilson came, examined them and said, ‘It’s diphtheria. All we can do now is hope . . . They might get better, they might get worse. I can’t tell.’ “He came again the following morning and just shook his head . . . “It was Freddy who first stopped breathing. I can still see Mother touching Freddy’s forehead and saying, her voice shaking and the tears coming down her face, ‘He’s cold … our Freddy is gone…’

The Lincoln Book

“Em was a strong, fine boy, and we hoped he might pull through. We stood by his bed and watched … His breathing came slower and slower, and in less than half an hour, he seemed to have stopped breathing. Mother put her hands on him and said, ‘Oh God, Emil is gone, too…”

“That was medicine in the late 1880’s. Look at it now. Why, nowadays, Freddy and Emil would be up and about in less than a week.”. After a long silence, Sandburg spoke up again.

“Speaking about children,” he began, “once upon a time, I had a brainstorm. I decided I would write a book that kids could understand and enjoy. It dawned on me that someone ought to tell them about that strange man from the plains of Illinois named Abe Lincoln. So, I sat down and wrote the title page — THE STORY OF ABRAHAM LINCOLN — FOR THE VERY YOUNG. . .

“It was my intention to write a short book, not more than three hundred pages. I thought I could write it, maybe, in six months. I didn’t want to write anything about the Civil War. I thought it would be too gory for the kids. I was going to say on the first page, “You all know about the great Civil War. I am not going to say anything about it in this book, but I want to tell you the story of Lincoln when he was still a young man and lived in a prairie town. ..’””

Gathering Information

He laughed and nudged his companion. “Well sir, then I began gathering my ammunition … Weeks, months,. years went by. Every day, I would find either a letter that was never published before, or a clipping, or a photograph that nobody before paid any attention to. It took me eight years before I was ready to- write my story. By that time, I could hardly move in my attic. Every inch of space was taken by boxes, barrels, and trunks containing my data. “As far as the actual writing was concerned, it took me exactly sixteen years to write “The Prairie Years’ and “The War Years.’ All in in all . . .” he laughed again, “well, the first World War was still on when I conceived the bright notion of writing ‘Abraham Lincoln’s Story for the Very Young,’ but by the time I finally managed to deliver the last batch of stuff to my publishers, it was July, 1939, and the second World War was just around the corner … Lordy, Lordy, how I worked. Often sixteen, sometimes as many as twenty hours at a stretch … My bones ached.

“I guess what actually kept me alive during those years was the challenge . . . When I started gathering my ammunition, I said to myself, ‘Let’s find out whether that man, Lincoln, was really as good and as great as they say.’ That was the challenge. “Well, Lincoln won. It took me twenty-four years to find out that he was every inch as good and as great as he was described.”

By now, Sandburg was within a block of his hotel. He stopped, lit a cigar, and spoke briefly of his new book. It is called, “Always the Young Strangers,” and Harcourt, Brace will bring it out on Tuesday, the poet’s birthday. It’s about the first 20 years of his life. He said he had to write it. There was no other way to “get rid” of the teeming memories of his past.

The Life of Riley

“There I was,” he said by way of explanation, “hibernating on my farm in Flat Rock, which is probably the smallest and the nicest town in my adopted State of North Carolina. I was living the life of Riley, staring at the Great Smoky Mountains, and watching my sixty goats that I brought with me from my farm in Michigan. “But my mind was far, far away, right back where I started from, in Galesburg, the town I was born in. … I would close my eyes and visualize the old burg as I knew it.

My father and mother, my sisters and brothers, the man who gave me my first job as a delivery boy … and the man who gave me hell because, instead of using a soft brush on his high silk hat, I dusted it with my whiskbroom … my school teachers and friends, and the storm. ..’” the Knox College campus where Lincoln and Douglas debated . . . Finally, it got too much for me. So, two years ago, I decided to re-visit Galesburg and maybe write a book about those far-gone days. “All the streets in Galesburg were paved by now, and the town looked happy and prosperous. Most of the people I knew were gone, but my cousin, Charlie Krans, with whom I played when we were kids, was still alive. So, I spent a day on his farm. When I was leaving, I said, ‘I think we’ll meet again, Charlie, we’re too ornery to die soon.’ ”

Never Lost Faith

Sandburg laughed uproariously. He was standing on the sidewalk in front of his hotel by this time and was about to go in when he suddenly changed his mind, turned around and looked at the lateafternoon sun that seemed to be setting afire the skyscrapers on lower Manhattan. His manner changed abruptly. He was no longer a jovial man who had gone to visit his old home town. His pale blue eyes were blazing, his finely chiseled face was set. He was a prophet. “I have spent,” he said gravely, “as strenuous a life as any man surviving three wars and two major depressions, but never, not for a moment, did I lose faith in America’s future. Time and time again, I saw the faces of her men and women torn and shaken in turmoil, chaos, and storm. In each Major crisis, I have seen despair on the faces of some of the foremost strugglers, but their ideas always won. Their visions always came through. “I see America, not in the setting sun of a black night of despair ahead of us, I see America in the crimson light of a rising sun fresh from the burning, creative hand of God. I see great days ahead, great days possible to men and women of will and vision. . . “” He took off his hat, as if saluting the future, and ran his hand through his white hair and said with a smile, “May I offer my favorite toast? “To the storms to come and the stars coming after.”

The End